The Three Cities Within Toronto > Toronto: A city of disparities

10. Toronto: A city of disparities

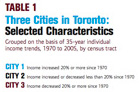

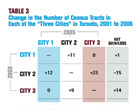

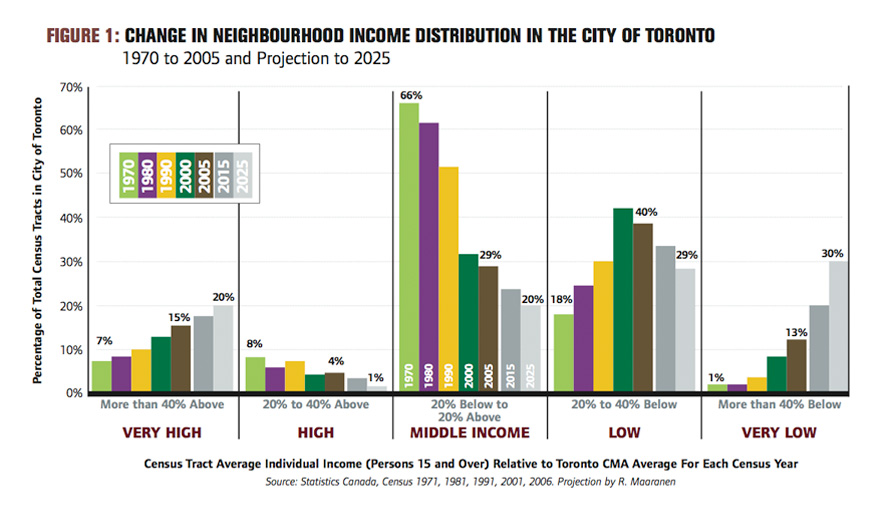

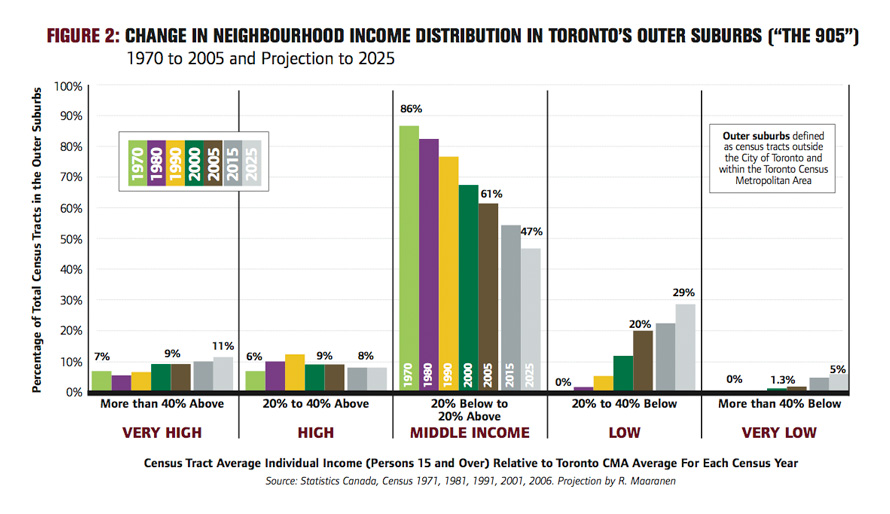

Toronto has changed, and continues to change, in terms of who lives where on the basis of residents’ income and demographic characteristics. Over the 35 years of this study, the gap in incomes between rich and poor grew, real incomes for most people did not increase, more jobs became precarious (insecure, temporary, without benefits), and families living in poverty became more numerous (as the 2007 United Way report Losing Ground documents). These general trends have played themselves out in Toronto’s neighbourhoods to the point at which the city can be viewed as three very different groups of neighbourhoods — or three separate cities. This pattern did not exist before. At the start of the 35 years, most of the neighbouhoods in the city, and more of the people living in the outer suburbs (the “905 region”) were middle-income (that is, they had incomes within 20% above or below the Toronto CMA average). In 1970 a majority of neighbourhoods (66%) in the City of Toronto accommodated residents with average incomes and very few neighbourhoods (1%) had residents with very low incomes (Figure 1 and Map 2). By 2005, only a third of the city’s neighbourhoods (29%) were middle-income, while slightly over half of the city’s neighbourhoods, compared to 19% in 1970, had residents whose incomes were well below the average for the Toronto area (Map 3). It is not the case that middle-income people in the city have simply moved to the outer suburbs (the “905 region”), since the trends are largely the same in those areas too (Figure 2). It is common to say that people “choose” their neighbourhoods, but it’s money that buys choice. An increasing number of people in Toronto have relatively little money and thus fewer choices about where they can live. Those who have money and many choices can outbid those without these resources for the highest-quality housing, the most desirable neighbourhoods, and the best access to services. When most of the population of a city is in the middle-income range, city residents can generally afford what the market has to offer, since they make up the majority in the marketplace and therefore drive prices in the housing market.A warning ignored: The metro’s suburbs in transition report

Download the reports

Metro Suburbs in Transition: Evolution and Overview, Background Report, 1979

Part 1, to Chapter 6

Part 2, Chapter 7 to end

Planning Agenda for the Eighties: Metro Suburbs in Transition, Policy Report, 1980

Part 1, to Chapter 5

Part 2, Chapter 6 to end

Download the reports

Metro Suburbs in Transition: Evolution and Overview, Background Report, 1979

Part 1, to Chapter 6

Part 2, Chapter 7 to end

Planning Agenda for the Eighties: Metro Suburbs in Transition, Policy Report, 1980

Part 1, to Chapter 5

Part 2, Chapter 6 to end

The post-war suburbs assumed one set of family conditions for child-rearing, and the physical environment incorporated these assumptions. The prototype suburban family — father in the labour force, mother at home full-time, ownership of a ground level home with private open space, two to four children, homogeneous neighbours — is no longer the dominant reality of suburban life in the seventies. It is now an image that belongs to the social history of the post-war period of rapid growth. (p. 236)It is these postwar suburbs that now form much of City #3 — the concentration of people with incomes well below the area average, an urban landscape that has a 30-year history of abandonment by people who have a choice. The start of this process was already clear by the late 1970s. The 1979 report concludes:

The traditional suburban neighbourhood may remain physically intact, but it is no longer the same social environment as in earlier days. Within it, around it, at the periphery, in local schools, in neighbourhoods nearby, are the visible signs of social transformation. The exceptions have continued to grow. There reaches a stage when the scale of the exceptions can no longer be ignored for established earlier settlers. Nevertheless, we would conclude that the social minorities taken as a whole now constitute the new social majority in Metro’s post-war suburbs. (p. 236)The shift from a traditional postwar suburban environment in the 1970s resulted largely from the development of high-rise apartment buildings, including many that contained social housing, and the consequent shift in social composition. Many census tracts included two contrasting urban forms — high-rise apartments on the major arterial roads and single-family, more traditional suburban housing on quieter residential streets. Over the ensuing decades, particularly in Scarborough, western North York, and northern Etobicoke, high-rise housing became home to many newly arrived, low-income immigrant families that came to Canada as a result of the shift in immigration policy in the late 1960s and early 1970s. In 2005 the City of Toronto and the United Way of Greater Toronto identified 13 “priority neighbourhoods” — areas with extensive poverty and without many social and community services. All 13 are in the “inner suburbs” and were the subject of the 1979 Social Planning Council report. City #3 includes the 13 priority neighbourhoods.

Figure 1, PDF

Figure 1, PDF

Figure 2, PDF

Figure 2, PDF