02. How and why do neighbourhoods change?

Neighbourhoods are complex blends of physical, social, and psychological attributes. Each neighbourhood provides different access to physical infrastructure and social and community services. Each has its own history. Each is the outcome of an ongoing process of collective action involving various social, political, and economic forces, both internal and external. These processes lead to neighbourhood change.

The price of housing is a key determinant of neighbourhood stability or change in societies where the real estate market largely governs access to housing. Higher-income households can always outbid lower-income households for housing quality and preferred locations. If a lower-income neighbourhood has characteristics that a higher-income group finds desirable, gentrification occurs and the original residents are displaced. The opposite also occurs. Some neighbourhoods, once popular among middle- or higher income households, fall out of favour and property values fail to keep up with other neighbourhoods. Over time, lower-income households replace middle- and higher-income households.

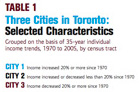

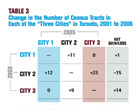

All these processes can be observed in the “city of neighbourhoods.” Rapid growth and a culturally diverse population have affected not only Toronto’s performance in national and world arenas, but also its neighbourhoods. In the 35 years between 1970 and 2005, the incomes of individuals have fluctuated, owing to changes in the economy, in the nature of employment (more part-time and temporary jobs), and in government taxes and income transfers. These changes have resulted in a growing gap in income and wealth and greater polarization among Toronto’s neighbourhoods.

What is a neighbourhood?

There is no one way to draw boundaries that define specific neighbourhoods. Defining a neighbourhood is, in the end, a subjective process. Neighbourhoods encompass each resident’s sense of community life. There is no doubt, however, about the importance of neighbourhoods and their effects on health, educational outcomes, and overall well-being.

For statistical reporting and research purposes, Statistics Canada defines “neighbourhood-like” local areas called census tracts. In defining census tracts, Statistics Canada uses recognizable physical boundaries (such as roads, railway lines, or rivers) to define compact shapes, within which can be found a more or less homogeneous population

in terms of socio-economic characteristics. The population of a census tract is generally 2,500 to 8,000. The City of Toronto encompasses 531 census tracts (as of the 2006 Census). Each has an average population of about 4,700 people. “Census tract” is used here interchangeably with the term “neighbourhood.”

In this study, our definition of a “neighbourhood” differs from that of the City of Toronto, which has defined and named only 140 neighbourhoods. Each represents a group of census tracts — on average, 3.8 census tracts and about 17,900 people. The city’s definition of neighbourhoods helps define and provide names for districts within the city, but they are too large to represent the lived experience of a neighbourhood. Individual census tracts come closer to that experience, even though they are statistical artifacts and do not always capture the true notion of neighbourhood.